Ten-year-old Katie smelled the bread sample, thought for a moment, and wrote a number on the printed sheet. She could have been in science lab, except for the fact that her teacher Mme. Clivaz was speaking French. “Sentez! Touchez! Goutez!,“ These students were using their senses to test the quality of the French baguette.

Earlier that week the fifth graders at Avery Coonley School in suburban Downers Grove had watched a YouTube video interview with Djibril Bodian, the Montmartre baker who has won The Best Baguette in Paris competition twice in the last decade (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K7N.) They watched as he handled each loaf and listened as he described how attention to detail, patience and sheer repetition made his baguette better than more than 100 others. How can there be that much variety in bread that consists simply of flour, water, salt and yeast?

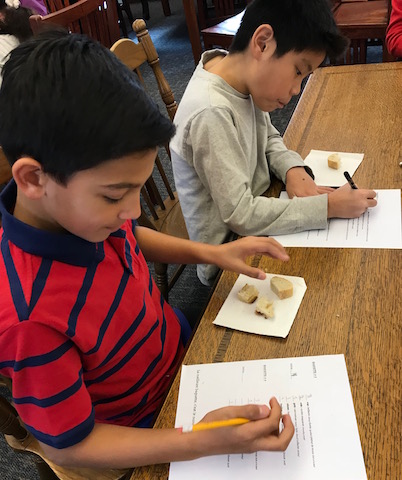

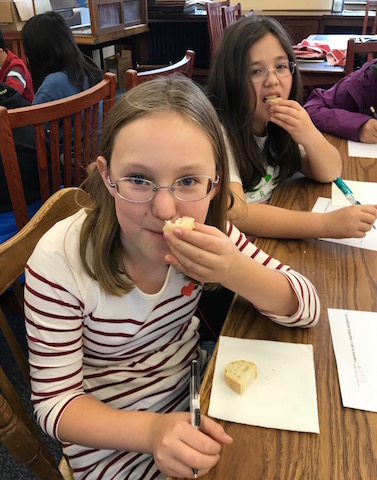

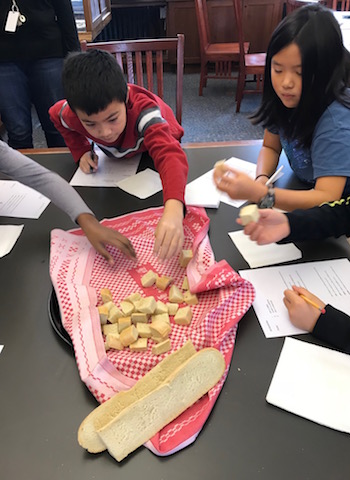

To prepare for a baguette tasting the students learned the French terms for their five senses as well as key words to describe each sense. By the time I arrived they were ready to judge four examples Mme. Clivaz and I had purchased. Together they observed the bread crusts for color and thickness (thin is better than thick). They listened for a cracking sound when the bread was broken. They all sniffed their samples for aroma, prodded, squeezed and tasted for texture and flavor. One loaf of each sample was halved lengthwise so they could examine its trous, the complex web of holes that indicates a perfectly risen loaf.

The students’ favorite baguette was one from Labrea Bakery (sold at Jewel/Osco) followed by La Fournette (1547 N. Wells, Chicago), Whole Foods and the Jewel bakery brand. Spoiler alert: The Labrea and La Fournette baguettes were made with a starter which gave them a flavor edge over those with dried yeast. The La Fournette baguette had a discernable tang which was less appealing to the young palates, although it had won a Best Baguette of Chicago competition at Hotel Sofitel in 2017. Taste aside, the crusts and interiors of the Whole Foods and Jewel’s loaves did not measure up in quality to the other two.

With their mission completed, the class relaxed and watched as classmate, Genvieve, demonstrated a dessert of colored grapes and dried fruits strung on a skewer (brochette de fruits). They quickly assembled colorful batons and carried the remaining baguette samples to lunch with them. Mme. Clivaz and I swept up the crumbs.

The Back Story: This novel experiment for fifth graders in suburban Chicaog is modeled on an annual event in France called La Semaine du Goût.. During a specified week in October, food and health professionals visit elementary classrooms to demonstrate their skills and speak of their passion for their calling. In this way the French reinforce their cultural values at a time when more industrial food products are available to tempt busy parents to take shortcuts.